In the previous blog we looked at how things are identified (i.e. how they’re unique) based on spatiotemporal criteria. Two things cannot occupy exactly the same chunk of space-time, or more accurately, that means they’re just one thing, and perhaps you have more than one name for it.

That’s fine for the physical stuff, but what about types of things ? Categories, sets, classes. In the various 4D ontologies that have been published, these terms have been used quite liberally with not much attempt to distinguish between them — though there are papers on this on the BORO site which provide a proper treatment. One possible reason is that the original authors of those ontologies were dabbling with different approaches to see which ones fitted the 4D approach best. There was general set theory, category theory, and Martin Löf type theory, just to mention three intersecting theories (see what I did there ?) All of these have sets as their base, and so do the 4D ontologies. If you thought it was somewhat counter-intuitive to identify things by their spatio-temporal extent (see previous blog), this topic might require even more unlearning of your preconceptions. Here we go.

Types (or classes) are also extensional in BORO — their identity is defined by their membership. They are sets of things. If two sets have the same members, they’re the same set. You might have more than one name for it, but as far as BORO is concerned, that’s one set. Just as with spatiotemporal individuals, you can have more than one name for the same thing. The morning star and the evening star are in fact the same thing — they’re both Venus. In an extensional ontology, there is one individual, and several names for that individual. The same thing happens with sets. If we have a set of all equilateral triangles, it’s membership is identical to the set of all equiangular triangles. In an extensional ontology (and all 4D ontologies are extensional) there is one set with two names.

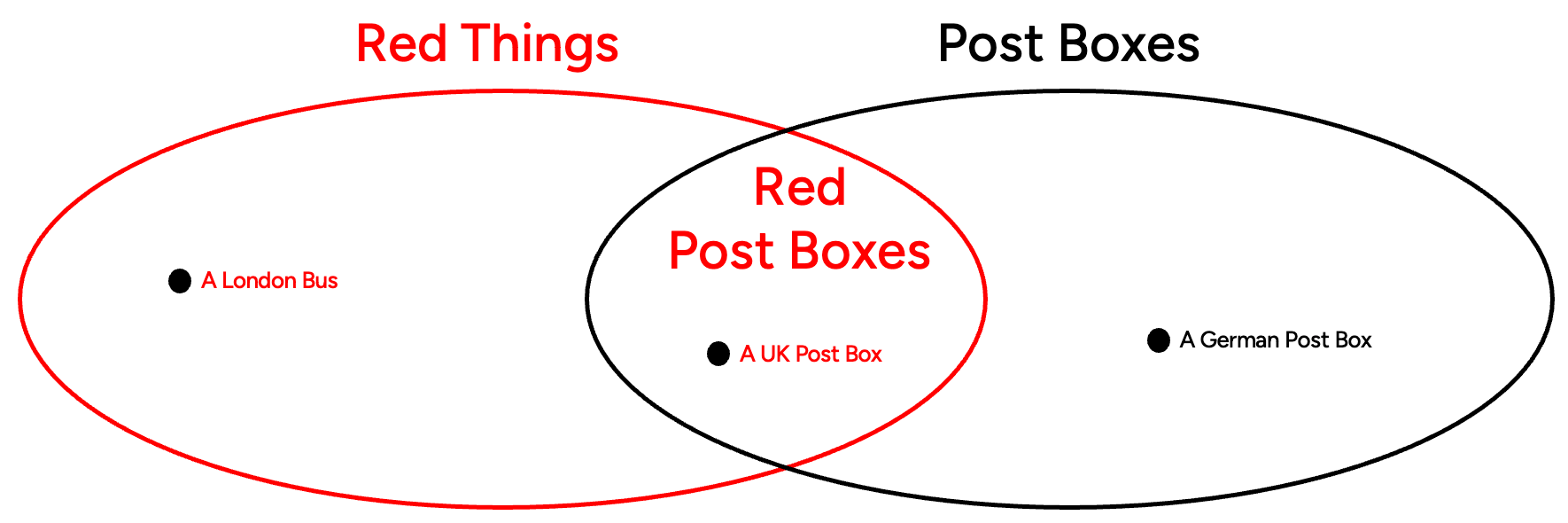

Sets can intersect. We can have the set of all red things, and set of postboxes. Where they intersect, there is set of red postboxes. Intersection means that they share some members — some postboxes are red and some red things are postboxes.

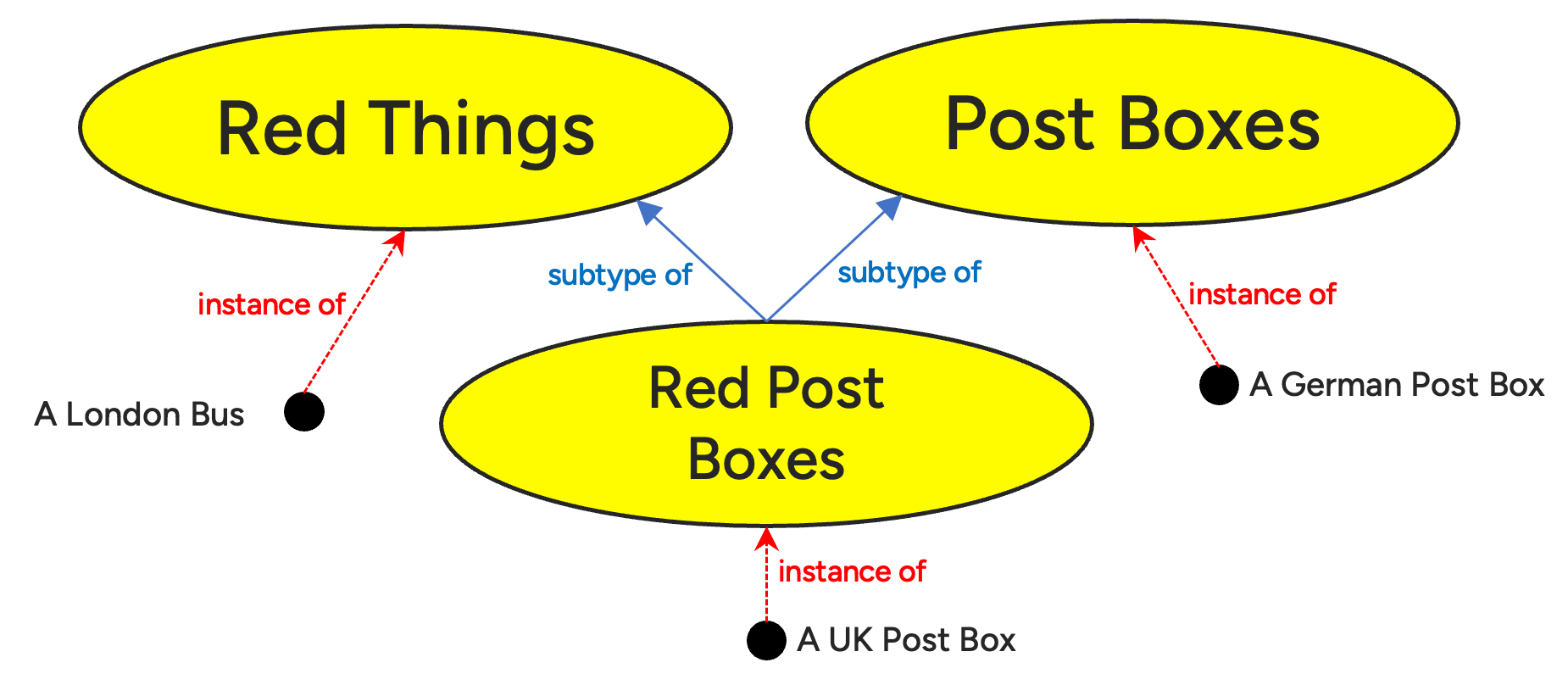

Now we’ve established that sets can intersect, we can deduce that some some sets are subsets of others — red postboxes is a subset of the red things set. It is also a subset of the postboxes set. There is a subtype relationship between these broader and narrow sets, and all ontologies do a lot of subtyping.

As well as the subtyping relationship, the diagram above also shows an instance of relationship — this relates the sets to their members. Most ontologies are developed using RDF Schema from the W3C. The IES ontology is a 4D ontology that uses RDF Schema. A set in IES is an rdfs:Class, and the rdfs:subClassOf relationship provides subtyping. These RDF Schema concepts are a bit broader than intended by a 4D Ontology, but the advantages of re-using a well implemented standard outweighed philosophical purity. IES also uses rdf:type for the set membership relationship.

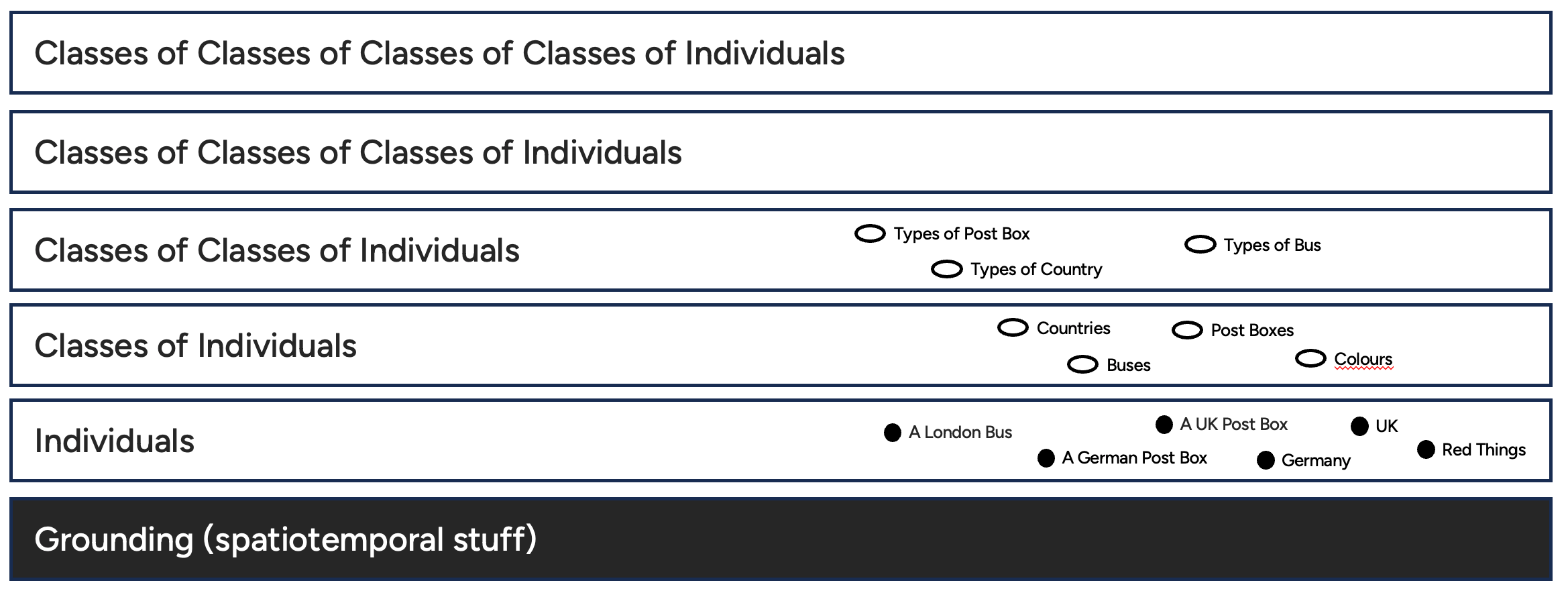

The really neat thing about having an extensional approach to individuals and sets means you can ground your ontology in reality. While this sounds like an obvious thing to do, you’d be surprised by how many ontologies only commit to the concept of an empty set and derive everything from that. There are also a bunch of models out there claiming to be ontologies that are just random collections of classes and relationships with no formal underpinnings, but that’s another rant for another blog. BORO ontologies all start with spatiotemporal individuals and work up from there, layer-by-layer:

I’ve put in a few example instances in the bottom three class layers to help explain it. In the upper layers, it all gets a bit esoteric, and the higher order classes are really only used for logically constraining the foundations of the ontology…so no examples provided here. There is no limit to the number of layers, and each layer is connected to the previous by an instance-of relationship (rdf:type or ies:powertype in IES).

This blog is getting a bit long, so I’ll try to follow up as soon as possible with more on classes. But just to recap, by taking a fundamentalist extensional approach to the ontology, both in terms of spatiotemporal individuals and classes, we ground the ontology in reality and provide traceability back to that grounding from even the higher order sets shown in the diagram above. A lot of ontologists don’t like to do what we’ve done here. They just want to have two layers — individuals and classes — as certain types of software reasoners can struggle to compute over such structures. The world is higher order though, and BORO ontologies favour high fidelity models of reality to the exclusion of a small set (of mostly academic) technology. There are ways to fool reasoners into thinking 4D ontologies are “flat earth” though, and it may be worth covering implementation tricks like that at some point in the future.